This photo shows the view from the maximum-security Ellis Unit prison in Huntsville, Texas. Once the site of Texas’s death row unit, infamous enough for musician Steve Earle to immortalize it in his song Ellis Unit One, it now houses the Champions Youth Program. This program supports male minors who, though tried as adults under Texas law, are housed separately from adult inmates as required by federal law.

Neuhaus Education Center was invited to partner with another nonprofit, Houston ReVision, to address the reading struggles many of the young men in the Champions Youth Program face. Houston ReVision’s mission is to break the cycle of juvenile justice system involvement and homelessness among youth in Harris County, Texas. During an initial visit, which included pizza and activities, the teens shared details about their lives. One 15-year-old, incarcerated since eighth grade, explained that he would remain in this unit until moving into the general population on the day he turned 18. Another said I reminded him of his auntie.

After my first visit, ReVision staff asked what I thought. My first words were, “They’re just kids.” Having worked in high schools for a decade, any one of them could have been my student.

In the days that followed, questions began to surface:

How are prison literacy screeners across decades still consistently revealing that many in this population lack functional literacy and show signs of dyslexia (Moody et al., 2000; Cassidy et al., 2021)?

How is dyslexia still considered a “disability of privilege,” in which families who have the means to access interventions and support produce future entrepreneurs, while those without such resources are statistically more likely to have their child end up in Ellis Unit?

Lack of Awareness

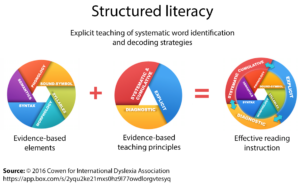

One explanation could be lack of awareness. Despite the overwhelming scientific consensus on best instructional practices for reading, also referred to as Structured Literacy (see: Moats, 2019), many instructors remain unaware and continue to use ineffective methods to teach reading. Dyslexia affects 5%–17% of the population (Wagner, 2020). This range stems from a lack of consensus on the definition of dyslexia and because the condition exists on a continuum from mild to severe. However, even if you ascribe to the most conservative end of that range, many states are not even identifying 5% of their population. In my home state of Texas, for example, 5.5% of students were identified in 2022–2023 (we finally crossed above that 5% threshold). Yet, in the Houston region in 2022–2023, only 4.6% of students were identified (TAPR Reports). Students with dyslexia are being missed.

At the Margaret H. Ley Adult Literacy Program at Neuhaus Education Center, we offer free in-person and virtual classes for learners with dyslexia and related reading difficulties. These classes are taught by licensed dyslexia therapists, a master’s-level licensure requiring 200 hours of coursework plus 700 supervised clinical hours. We serve a diverse range of people starting at age 16—including language learners with English conversational proficiency. All share one commonality: they are of average to above-average intelligence but read at kindergarten to third-grade level. The majority have high school diplomas, yet they are not functionally literate. Our learners include everyone from those who did not finish formal schooling to former NASA employees. They are brilliant, resourceful, brave, and creative. As one student put it, “I can build your dream house tomorrow; just don’t ask me to write the receipt for it.”

You see, here’s the thing about reading: The Simple View of Reading explains that reading comprehension depends on two equally important components—decoding and language comprehension. These components work together, and without one, true reading comprehension is not possible. We naturally develop language comprehension—our brains are wired for it. In most cases, a baby exposed to conversation will “pick it up.” But put that same baby in a room full of books, and they won’t walk out reading. As Maryanne Wolf explores in her book Proust and the Squid, our brains aren’t wired for reading; it must be explicitly taught.

Some joke that before books, people with dyslexia ruled the world with their creativity and intelligence. Only language comprehension was truly required. However, the Gutenberg press changed everything. Suddenly, decoding became essential, and it is this decoding skill that often poses a core difficulty for those with dyslexia.

The Facts

In honor of Dyslexia Awareness Month, here are critical facts for you to know and share:

Dyslexia is more common than you might think.

There are people in your life and learners in your program who have dyslexia, even if you may not know who they are.

Dyslexia is often unexpected.

Typically found in those with average to above-average intelligence, dyslexia can often be missed. It is hard to understand why someone who seems to verbally “get it” can struggle so much with literacy tasks. Many of our Neuhaus adult literacy students share that they have been told to “try harder” throughout their education. For a highly capable student who is aware of their struggles, this type of feedback can lead to severe, life-threatening mental health developments over time. Many of our adult literacy students are battling acquired anxiety and depression.

Family history matters.

Dyslexia has a strong genetic link. If an adult in your program is struggling with reading and has a child, make them aware of this genetic link. Check on the child’s reading progress as well. In the Houston area, adults who would like support with their child’s reading journey can contact Neuhaus’s Family Support Office, which provides free consultations, in English and Spanish, to empower families to advocate for their child. It is essential to empower our adult learners to break multi-generational cycles of low literacy.

In adulthood, untreated dyslexia can present as difficulties across all academic areas.

The Matthew Effect posits that initial reading struggles, if untreated, compound over time due to less practice with reading and thereby less exposure to vocabulary and background knowledge. This can result in testing that shows lower scores due to a lack of reading experiences, not actual intellectual ability.

It is never too late.

Just ask our 90-year-old student, who wanted to learn to read so that he could read to his grandchildren. Structured Literacy is an effective approach across age groups and learner types. We must meet all readers at their reading stage, with age-appropriate materials. In our adult literacy program, we use a curriculum called Structured Reading and Spelling, which was specifically designed for high school and adult learners and follows the principles of Structured Literacy.

Your role matters.

In Houston, 1 in 3 adults lack functional literacy (Houston’s Adult Literacy Blueprint, 2021). Consider the last time you ordered off a menu, read a road sign with a traffic update, or signed a form from your child’s school. One in three Houstonians (and one in five adults across the United States) struggle with those tasks. For Houston, moving one-third of our population to literate would realize over $13 billion in economic gains (Gallup, 2021). Not everyone is called to directly support adult literacy students through instruction, but consider also volunteering with local literacy groups, providing financial support, or inviting literacy advocates to your workplace to raise awareness and drive change.

Lastly, I urge you to consider that, in our society, literacy is necessary to survive. Ensuring that all people have access to high quality and skilled instruction in reading before life-altering consequences occur is the civil rights issue of our time. I hope you will thoughtfully consider where you can strategically employ your talents and unique offerings to bring this into reality.